The Counsel of Vyasa: Dharma and the Burden of Kingship

- Anaadi Foundation

- Sep 5, 2025

- 5 min read

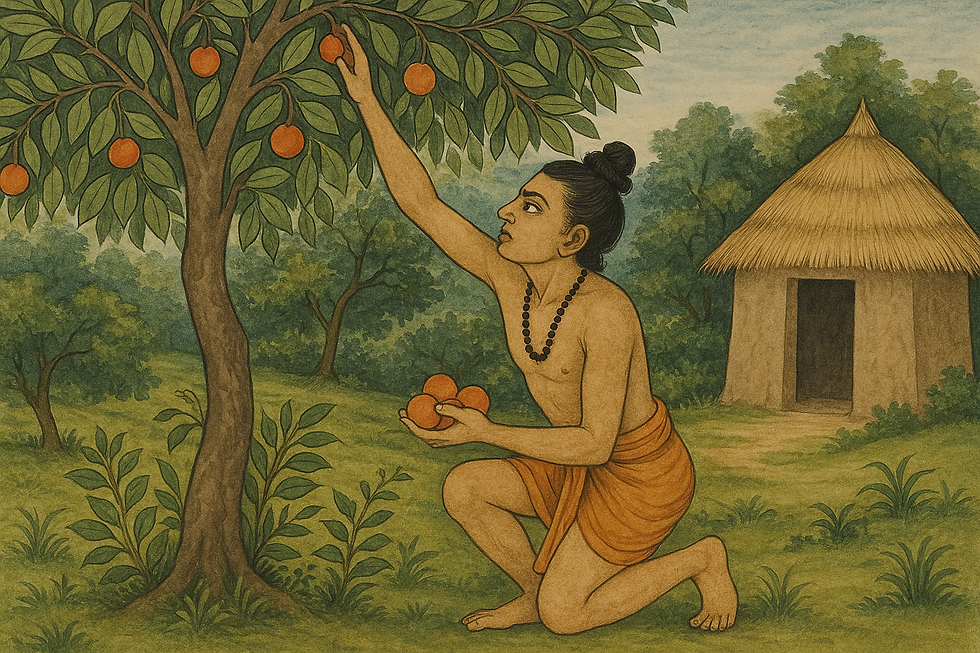

Story of Sankha and Likhita

The Rājadharmanūśāsana Parva is one of the smaller parvas of the Śānti Parva in the Mahābhārata. It comes immediately after the war, when Yudhishthira, overwhelmed by grief and guilt at the destruction caused, wishes to renounce kingship and retire to the forest.

Arjuna Tries to Console Yudhishthira

Arjuna tried to console his elder brother Yudhishthira, who was sunk in grief. He reminded him that as a Kshatriya, he had fulfilled his duties by winning sovereignty, a goal very difficult to attain, and by conquering all his enemies. Arjuna questioned why, despite such accomplishments, Yudhishthira continued to burn in sorrow.

He explained that for Kshatriyas, death in battle was considered more sacred and rewarding than even the performance of sacrifices. Scriptures clearly state that penance and renunciation are the duties of Brahmanas, while fighting and dying in battle are the ordained duties of Kshatriyas. Their lives are tied to weapons, and when the time comes, they are expected to perish in battle. Even if a Brahmana lived by Kshatriya duties, such a life was not considered blameworthy, for Kshatriyas themselves had sprung from Brahmanas.

Arjuna reminded Yudhishthira that renunciation, sacrifices, penance, or dependence on the wealth of others were not prescribed for kings of the warrior class. Yudhishthira, being well-versed in all duties and wise in judgment, should rise above despair, strengthen his will, and engage in action. The heart of a Kshatriya, Arjuna said, was meant to be as firm as thunder. Having already subdued his enemies and secured a peaceful empire, Yudhishthira should now turn his energies toward conducting sacrifices and giving in charity, thus purifying himself.

Arjuna pointed to Indra as an example. Though born a Brahmana, Indra took on the duties of a Kshatriya, fought against his sinful kin in hundreds of battles, and through such actions attained the supreme position among the gods. Yudhishthira, too, should perform great sacrifices and offer gifts in plenty, thereby freeing himself from grief.

Arjuna concluded by reminding his brother not to lament the past. Those who had fallen in battle had attained the highest end, sanctified by weapons in line with Kshatriya dharma. What had happened was destined to happen, and destiny, he said, could never be resisted.

Vyasa Counsels Yudhishthira

When Arjuna spoke firmly to his elder brother, Yudhishthira fell silent, unable to respond. At that moment, Vyasa stepped forward with words of guidance.

Vyasa affirmed Arjuna’s counsel: “What Arjuna has spoken is indeed true, O Yudhishthira. The highest dharma, as revealed by the scriptures, is rooted in gṛhastha āśrama—the life of a householder. You are already well-versed in all duties, and it is this path of domestic responsibility that you must uphold. Renunciation of household duties and retreat to the forest is not ordained for you. The gods, the ancestors, guests, servants, birds, animals, and countless beings all depend upon the householder for their sustenance. For this reason, the way of the householder is considered superior, though it is the most challenging of all the four āśramas. Only those with great restraint can live such a life with dignity and integrity.

You are learned in the Vedas and have already gathered much ascetic merit. Now, like a steady ox that bears the yoke, it is your duty to carry the burden of your ancestral kingdom. The sages have laid down different disciplines for Brahmanas—penance, sacrifice, self-restraint, forgiveness, learning, mendicancy, contemplation, solitude, contentment, and knowledge of Brahman. These pursuits elevate them. But the duties of a Kshatriya are of a different order. They include sacrifice, study, exertion, ambition, the wielding of punishment, fierceness, protection of subjects, knowledge of the Vedas, penance, good conduct, acquisition of wealth, and charity to the deserving. Among these, wielding the rod of chastisement is said to be the foremost duty of kings.

Strength and authority are the foundation of a Kshatriya’s role, and discipline must flow from them. Vrihaspati once declared: “Like a snake devours a mouse, the Earth devours a king inclined only to peace, or a Brahmana overly attached to household life.” History too tells us that the royal sage Sudyumna achieved the highest success by wielding the rod of chastisement, much like Daksha, son of Prachetas.”

At this, Yudhishthira inquired, “O holy one, by what deeds did King Sudyumna earn such great success? I wish to know his story.”

Vyasa Narrates Story of Sankha and Likhita

Vyasa replied with an ancient tale.

There once lived two brothers of rigid vows—Sankha and Likhita—residing in two beautiful hermitages by the river Vahuda. One day, when Sankha was absent, Likhita came to his hermitage. Seeing ripe fruits hanging in abundance, he plucked and ate them without hesitation. When Sankha returned and found his brother eating the fruits, he asked sternly, “From where have you taken these?” Likhita admitted, smiling, that he had taken them from Sankha’s own retreat.

But Sankha grew angry. “You have committed theft,” he declared. “Go to the king and confess. Say to him, ‘I have stolen fruits not given to me. As a thief, punish me according to your dharma.’”

Obeying his brother, Likhita went to King Sudyumna and confessed. The king welcomed him respectfully and asked why he had come. Likhita replied, “I have eaten fruits that were not mine to take. O king, punish me as you would a thief.”

At first, Sudyumna offered pardon, reminding him that the king’s power to punish is also the power to forgive. But Likhita insisted. At last, the king ordered that both of Likhita’s hands be cut off. Bearing the punishment calmly, Likhita returned to Sankha.

“Now forgive me,” he said, “for I have been duly punished.” Sankha, filled with affection, replied, “I was never angry, nor have you wronged me. But your virtue had faltered, and through this, you are purified. Go now to the Vahuda and perform water-oblations to the gods, sages, and ancestors. Never again set your heart on sin.”

Likhita did so, and in wonder, found two new hands—like blooming lotuses—appearing where his stumps had been. Astonished, he returned to Sankha, who explained, “This is the fruit of my penance, though Providence has been its true cause. The king who punished you is purified, and so are you.”

Vyasa concluded, “Thus did King Sudyumna, by upholding the law of chastisement without favoritism, attain eminence and success like Daksha himself. This, O Yudhishthira, is the true duty of kings: to rule and to protect. Do not give in to despair. Heed your brother’s words. The king’s dharma lies in wielding the rod of justice—not in abandoning the crown for the shaven head of renunciation.”

Comments